Cheesecake Texture Calculator

Predicted Texture

Based on your selections

Ever cut into a cheesecake expecting a creamy, cloud-like slice, only to get something that feels like a brick? Or maybe you wanted a rich, dense bite, but ended up with something too light and airy? The difference between a dense and a fluffy cheesecake isn’t about skill-it’s about ingredients and technique. And once you understand how they work, you can control the texture every time.

It All Starts with the Base: Cream Cheese

Cream cheese is the heart of any cheesecake. But not all cream cheese is the same. Full-fat, brick-style cream cheese-like Philadelphia or Anchor-has about 33% fat and very little water. That’s what gives you that signature richness and structure. If you use low-fat or spreadable cream cheese from a tub, you’re adding extra moisture and air. That’s the first reason your cheesecake turns out fluffy instead of dense.

Brick cream cheese is firm, stable, and holds its shape when mixed. Tub cream cheese? It’s been whipped with air to make it spreadable. When you bake it, that air expands and creates bubbles. Result? A lighter, more sponge-like texture. For a truly dense cheesecake, stick to the block. Always.

How Eggs Change Everything

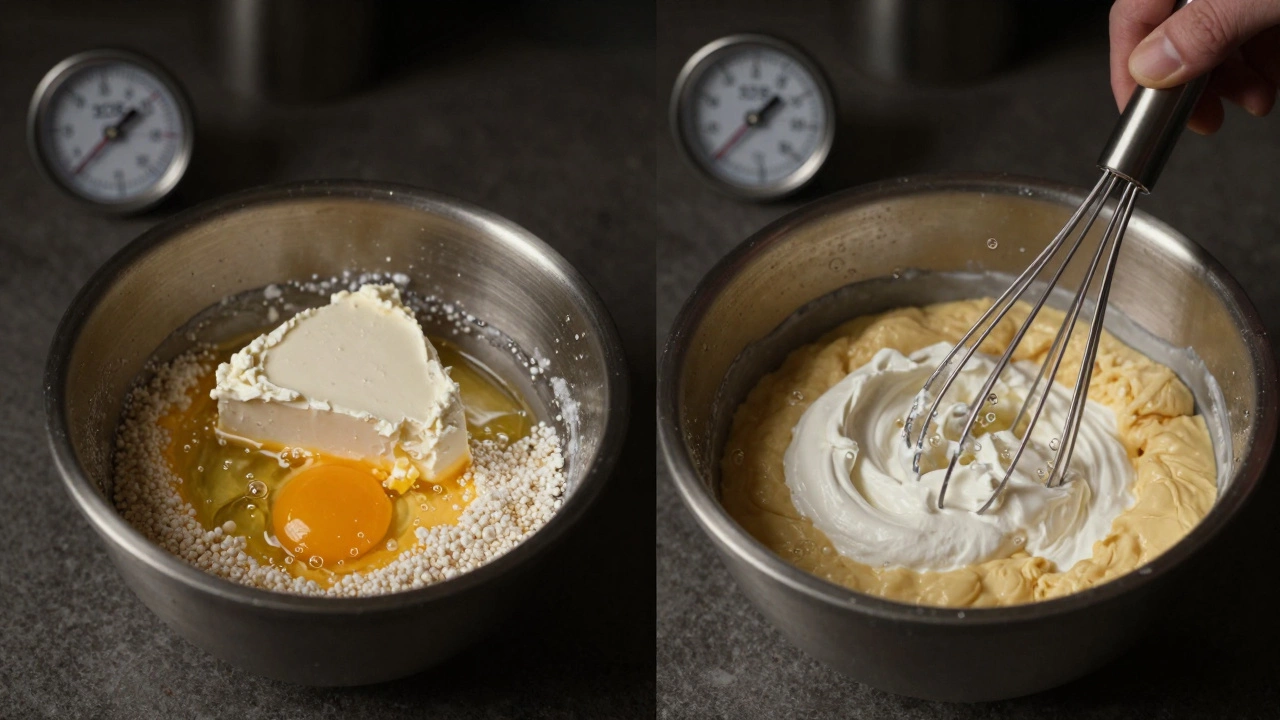

Eggs are the glue that holds cheesecake together. But they’re also the main reason for texture differences. Egg yolks are fat and emulsifiers-they make things rich and smooth. Egg whites? They’re mostly protein and water. When heated, those proteins tighten and trap air, making things rise.

A dense cheesecake uses mostly yolks or just whole eggs in small amounts. Think 2-3 whole eggs for a 9-inch cake. A fluffy cheesecake? It often has 4 or more whole eggs, sometimes even separated. The whites are whipped to soft peaks and folded in like a meringue. That’s how New York-style cheesecakes stay heavy, while Japanese soufflé cheesecakes puff up like a cloud.

If you want dense, skip the meringue. If you want fluffy, whip those whites. Simple as that.

The Role of Sugar and Flour

Sugar doesn’t just sweeten-it affects structure. More sugar means more moisture retention. That’s why caramelized, syrupy cheesecakes feel softer and more yielding. But too much sugar can weaken the protein network from the eggs, making the cake more fragile.

Flour is the hidden texture switch. A traditional New York cheesecake doesn’t use flour at all. It relies on eggs and cream cheese for structure. But if you add even a tablespoon of flour, cornstarch, or cake flour, you’re adding a stabilizer. That stops the eggs from over-expanding. The result? A denser, more compact crumb. It won’t crack as easily, either.

Want fluffy? Skip the flour. Want dense and crack-free? Add 1-2 tablespoons of cornstarch. It’s the secret behind bakery-style cheesecakes that hold their shape without being gummy.

Baking Temperature and Time

Heat is the invisible hand shaping your cheesecake. High heat (375°F / 190°C) makes the outside set fast while the center is still liquid. That forces the center to rise quickly-creating air pockets and a puffy top. That’s how you get a soufflé effect.

Low and slow (300-325°F / 150-160°C) is the key to density. The heat moves gently through the batter. The proteins coagulate slowly. Air bubbles have time to escape instead of getting trapped. The cake sets evenly. No puffing. Just smooth, heavy, velvety texture.

And don’t forget the water bath. Baking in a bain-marie adds moisture to the oven. That keeps the surface from drying out and cracking. But more than that, it slows down the cooking. That’s why professional bakers use it for dense cheesecakes-it’s not just for looks. It’s for control.

What Happens When You Overmix?

Overmixing is the silent killer of texture. Once you add the eggs, stop stirring. Whipping the batter too long-especially with a stand mixer-drags in air. That air turns into bubbles during baking. Even if you use the right ingredients, overmixing can turn a dense cheesecake into a fluffy one.

Think of it like pancake batter. You mix just until the flour disappears. No more. Cheesecake is the same. Mix the cream cheese until smooth. Add sugar. Then eggs, one at a time, on low. Just until blended. That’s it. If you see the batter looking glossy and slightly aerated, you’ve gone too far.

Chilling: The Final Texture Setter

People think the oven does all the work. But the fridge finishes it. A cheesecake needs at least 6 hours-preferably overnight-to fully set. Cold temperatures allow the fats to re-crystallize and the proteins to firm up.

If you cut into it too soon, it’ll feel soft, wet, or even runny. That’s not underbaked-that’s unsetting. A dense cheesecake will hold a sharp edge when sliced. A fluffy one will have a slight wobble, even after chilling. That’s normal. It’s supposed to be delicate.

Real Examples: What You’re Actually Eating

Let’s break down two popular styles:

- New York Cheesecake: Brick cream cheese, 3-4 whole eggs, no flour, low oven temp, water bath. Result: Heavy, creamy, almost custard-like. Slices cleanly. Sinks slightly under pressure.

- Japanese Soufflé Cheesecake: Brick cream cheese, 4+ whole eggs (whites whipped), no flour, high oven temp, no water bath. Result: Light, airy, jiggly. Slightly sweet, melts on the tongue. Looks like a cake that floated.

One uses the same base ingredients. The only difference? How they’re treated. That’s all it takes.

Quick Texture Cheat Sheet

Want to build your own perfect cheesecake? Use this as a guide:

| Goal | Ingredients | Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Dense | Full-fat cream cheese, 2-3 whole eggs, 1-2 tbsp cornstarch | Low oven (300-325°F), water bath, mix gently, chill overnight |

| Fluffy | Full-fat cream cheese, 4+ whole eggs (whites whipped), no flour | Higher oven (350-375°F), no water bath, whip whites, chill 6+ hours |

There’s no right or wrong. It’s about what you love. Some people want their cheesecake to stay on the plate. Others want it to disappear in one bite.

Common Mistakes That Ruin Texture

- Using low-fat cream cheese → too moist, airy, falls flat

- Skipping the water bath for dense cakes → cracks, uneven rise

- Overbaking → rubbery texture, even if dense

- Opening the oven door too early → sudden drop, collapse

- Chilling too fast (putting hot cheesecake in fridge) → condensation, soggy crust

One small change can flip the whole outcome. That’s why baking is science-and why your cheesecake doesn’t have to be a gamble.

Write a comment